How to Write Captivating Sentences

A writer might be describing the best thing since sliced bread, but if their sentences are dull, readers aren’t likely to stay engaged. The way the words sit on the page and on the tips of our tongue can enchant a reader.

Though some kinds of writing are meant to be perfunctory, there is room for art in many instances.

In this post:

The do nots

Sentence length

Syntax

Rhyme & alliteration

The exceptions

The do nots

Before we get into the techniques, let’s look at some of the habits that can weaken writing.

Too little variation

Our first attempt at writing often sounds the way we speak. There are variations to the sentence lengths or the way we position clauses. Sometimes if a writer over-edits their work, they can strip too many of these differences, making the writing monotonous.

Of course, there are rules to writing which are best to follow unless in special circumstances, but that doesn’t mean sentences must be formulaic. When composing, or especially when editing a sentence, make sure it doesn’t sound too similar to the ones surrounding it.

Verbosity

As Shakespeare once said, “Brevity is the soul of wit.” Some (and I have been guilty of this particular sin) expand their thoughts beyond what is necessary, often due to a concern that we won’t be understood, or occasionally because we just like the sound of our own voice.

Unfortunately, verbosity helps neither understanding (the longer something is, the more room there is for confusion) nor does it make us look intelligent (simple is almost always harder to pull off).

Keep an eye out for long-winded or run-on sentences in your work when editing.

Jargon or overly complex language

A cousin of the overly long sentence is the use of overly complicated language. Again, simple is hard to pull off, but there is beauty and understanding in simplicity.

If you want to work in the new word you got from your daily calendar, give it a shot, but make sure it’s clear to your readers. They’ll likely figure it out from context, but even a brief pause can pull a reader out of the writing. Additionally, the more complicated a word is, the harder it might be to apply the proper usage.

Phonetic spellings in dialogue

This dialogue quirk is uncommon in published writing, but it can be a pitfall, especially for newer writers.

“How do I let my readers know my character has a particular accent or speech pattern?” you might wonder. If you’re tempted to spell out your character’s speech phonetically, a couple things might happen:

Your readers will have to sift through this particular character’s dialogue each time they open their mouths (and quickly grow to hate them, whether or not that is the goal).

Reading the character’s parts can become virtually impossible for audience members with reading-related disabilities.

A reader who has this character’s particular accent could be offended with the portrayal.

So how do we answer that first question without causing this kind of harm? Here are some suggestions:

State that the character speaks with a particular accent. Unless it is relevant to your audience’s understanding of the plot, it’s unlikely that a character’s accent will have a big impact on their overall grasp or enjoyment of the story. Accents could add some immersion, but they’re best treated as window dressing. For a character to be well-rounded, we don’t especially need to know their accent.

Use the odd contraction (e.g., ain’t), slang or phrases particular to that character’s background. If sprinkled in sparingly these can serve as small reminders about the character’s voice. Just don’t overdo it.

There are other ways to distinguish your characters’ voices, or your own narrative voice, for that matter. We’ll take a look at some of these next.

Sentence Length

One of the best ways to add interest to your writing is to play with the lengths of your sentences.

If you have an exceptionally long sentence, maybe you want to follow it with a shorter one. Like this.

Want to sound staccato? Try short sentences. No lists. Nix multiple clauses.

Longer sentences, meanwhile, can present a meandering, perhaps even listless voice and tone. Be careful not to bore readers with these.

Keep an ear out for how you or others sound when speaking. Since we’re infrequently speaking to robots who spit out perfectly symmetrical sentences, you should notice an ebb and flow to the way people speak. That doesn’t mean your writing has to be a repeating ABABAB pattern (unless perhaps you’re writing in that specific poetic form). Embrace the organic movement of words.

Syntax

You can really spice things up by throwing in an interesting word every now and again. But careful—too much spice is unpleasant.

Rather than plundering the thesaurus, see if you already know a word that fits. Or maybe the word you’d like to use is better suited as a metaphor or other comparison. You don’t always have to use the word’s literal meaning, so long as it makes sense in context.

Beyond word choice, consider the length of your words themselves. We typically write with words that vary in length, but it doesn’t hurt to pay attention.

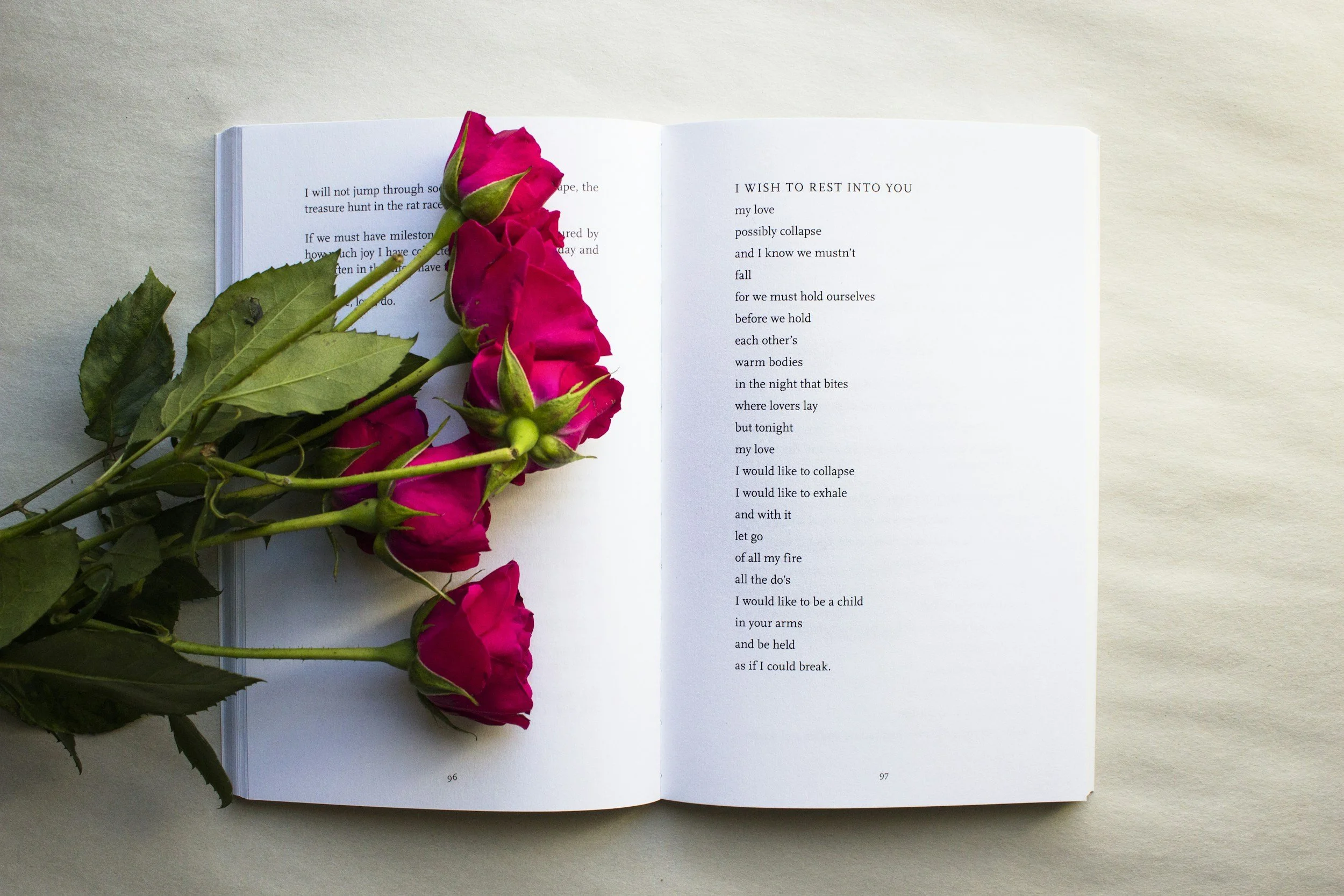

Rhyme & alliteration

These language elements are most often seen in poetry, though there’s no rule that they need to stay there.

Rhyme is helpful if you want the writing to sound playful or a little silly. A prime example can be found in the works of Dr. Suess. But rhyme needn't be unserious. If you want to add some poetic flow to your work, the odd internal or imperfect rhyme can help. Similarly, including symmetrical syllables or clauses in a sentence affects the flow.

“The mechanism ground to a halt, finished etching the image into the stone.”

Alliteration, using words that have the same beginning sounds, can give your work new life. For vowels this is called assonance and for consonants, consonance.

The example below contrasts a sentence with some minor alliteration with one that contains a more deliberate use of the device. Consider how the word choices here affect the sentence flow:

“It stayed like the last mound of snow on the yard.”

“It lingered like the last shimmer of snow on the yard.”

There is another poetic device in the second sentence if you read it through slowly. “Shimmer” and “snow” are words that both evoke a slight onomatopoeia for the element they describe.

The exceptions

The big caveat to remember here is that you always have freedom to play around with the language and see what works. You just have to weigh it against potentially turning your readers off.

If you want a certain character to sound curt, try making their sentences short and simple. If you want to draw particular attention to a theme, repeat a specific word a few times.

Trying to sound hard and industrial? Check for accidental alliterations or rhymes that could smooth out the flow too much.

Just remember, your style, while it can be beautiful, should never be a distraction.

The tools are all there for you to use. Give it a shot—try out some of the techniques listed (and maybe some that aren’t) and your words could soon be singing from the page.

Mary Kehoe provides structural, stylistic and copy editing services for a variety of written works through her agency, Elixir Editorial. From time to time she dabbles in her own writing projects which tend toward the speculative genre.

She is a member of both Editors Canada and the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP), as well as a founding member and former chair of the Toronto Arts & Letters Club writing group. A longtime lover of the English language, Mary is passionate about supporting writers on the journey to inspire the world.